Muslim Voices — Christiane Gruber

Audio transcript:

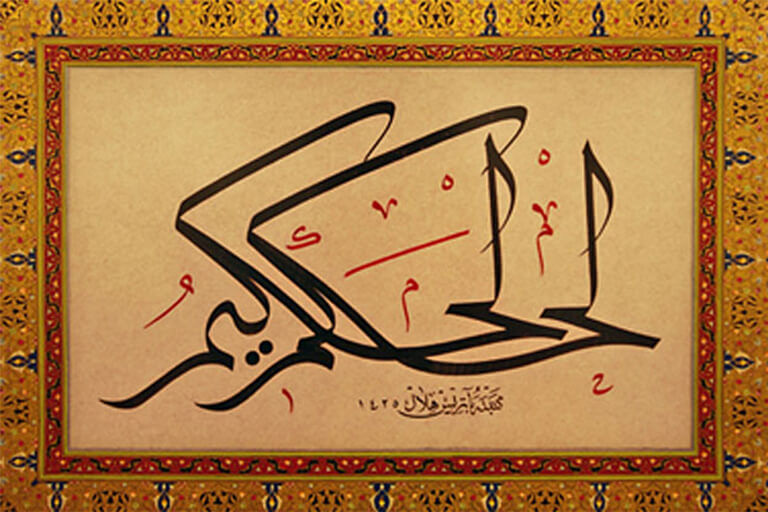

0:00:07:>>MANAF BASHIR: Welcome to Muslim Voices. I'm your host Manaf Bashir. Art has a rich history in the Muslim world. Both the festival as well as the visual arts have been praised by Muslim cultural. Examples of what some consider Islamic art are the desert mosque of Timbuktu in Africa, the Taj Mahal in India and multiple depictions of the Prophet Muhammad and Muslim texts. But even though these are examples of what Islamic art could be, trying to nail down just what makes art Islamic difficult. Although, as Indiana University's Christiane Gruber tells Rosemary Pennington, there is one art form that virtually every Islamic culture prizes - calligraphy.

0:00:49:>>CHRISTIANE GRUBER: Calligraphy itself is considered more or less an exercise in perfection. And calligraphers and writers themselves saw their task to be the perfection of the written form. In a way, it's a task that has a sacred dimension to it because God is described as he who teaches by the pen. In other words, his pen is also the pen of creation and the ink blot is likened to the primordial blood clot. In other words, it is the inception of all creations. That's one of the symbolic reasons why calligraphy has reigned supreme. The other reason - and this is what you hear most frequently - is that there is a ban on the figural arts in Islamic production. And this is a very slippery slope when we talk about a ban on figural production. There is no ban, persay, in the Quran. And even the references in the Hadith and the sayings of the Prophet give some sort of, let's say, there are prescriptions in the Hadith against the figural arts but these do not stand fast and firm. And over and over again in multiple Islamic traditions, we see that prohibition is not equal to practice. And so we do see figural forms - pictures and paintings emerge, especially in secular private domain. Certainly not in a mosque area - in a public area, though there are certain exceptions to that rule.

0:02:15:>>ROSEMARY PENNINGTON: So if you have a society that has accepted that, that we can create figural art, that we can depict human beings. Are there any steadfast rules as to who can be portrayed and how they can be portrayed?

0:02:29:>>CHRISTIANE GRUBER: There are no steadfast rules but there are certain developments that we can trace through time. If I were to pick for example, one case would be the image of the Prophet Muhammad. Right until about the 1450s in these Mongol societies of Iran, there are book arts that depict the Prophet in his full corporeal form with his visible features - his facial features fully visible. Sometime in the 15th century there's a switch and he starts to adopt a facial veil, so his facial features become covered. One of the reasons might be the growth of mysticism and the idea that the Prophet Mohammed is a primordial essence that's invisible to the human eye. At the same time, there might be other religious and political factors that lead to the gradual abstraction of his facial features. And then eventually, by the 1900s, especially in Persian and Turkish spheres where there were images of the prophet, the image of the Prophet begins to disappear. And that's really a modernist sort of neo-traditional - or reinvention of tradition about the Prophet Muhammad never being depicted at all. But this is of course a revisionist approach to the material.

0:03:44:>>ROSEMARY PENNINGTON: So why would figures be a problem? I mean, why would it be that you might find something in the Hadith saying you can't depict human beings. I mean, what's sort of the reason for that?

0:03:55:>>CHRISTIANE GRUBER: Well, this is a long-lived tradition, not just only in Islam but in Jewish and Christian traditions. It's a general fear of the power of the image to potentially come alive. And connected to that fear is the inclination of human beings to perhaps worship that figure rather than that which it represents. In other words, when you have a statuette or a little figure - especially of a prophet, a saint, the Prophet Mohammed or Jesus, whatever it might be - there's a fear that worshippers, devotees might be turning their attention to that representation which is, in a sense, a platonic removal of the essence which it represents.

0:04:43:>>MANAF BASHIR: Indiana University's Christiane Gruber talking about art in the Muslim world. Gruber is an assistant professor of Islamic art at IU. This has been Muslim Voices, a production of voices and visions in partnership with WFIU public media from Indiana University. Support for Muslim Voices comes from the Social Science Research Council. You can subscribe to our podcast in iTunes or join the discussion on our website. Find us online at MuslimVoices.org.

IU Global

IU Global