Muslim Voices — John Hansen

Audio transcript:

0:00:06:>>MANAF BASHIR: Welcome to Muslim Voices. I'm your host, Manaf Bashir

0:00:10:(MUSIC PLAYING)

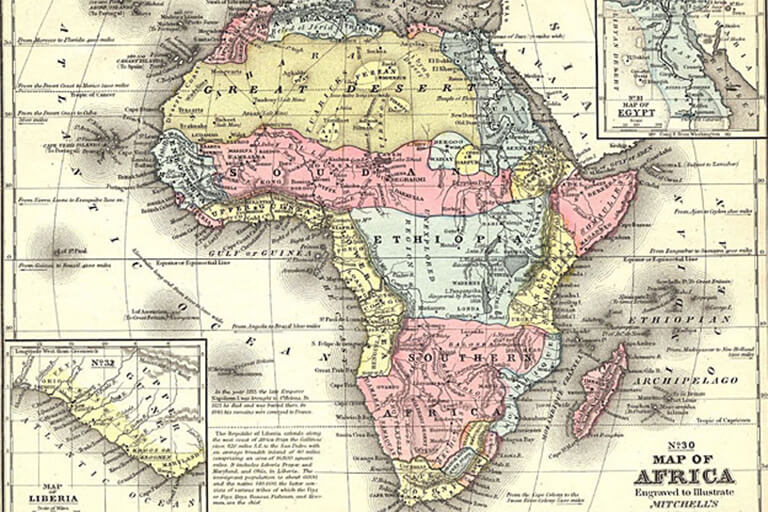

0:00:12:>>MANAF BASHIR: Islam has a long history in Africa. According to our tradition, the religion first arrived in Northern Africa with Muslims fleeing persecution on the Arabian Peninsula. Scholars believe it took centuries for Islam to take root in the region with North African Muslims eventually taken on practices of Arab culture. The region is often considered part of the Arab world. While Islam's expansion in North Africa was gradual, it was even slower in sub-Saharan Africa. Often, elites converted first, with the general population following much later. That's not the only difference, however. Sub-Saharan Muslims also tended to keep their traditional cultures intact, as Indiana University's, John Hanson tells Rosemary Pennington.

0:00:57:>>JOHN HANSON: Historians of religion would say that any religion that's going to become a world religion is going to have this kind of accommodation, that local people make the religion of their own and bring ideas from the great tradition and incorporate into local practice. And it's a synthesis and it happens in various religions. You see this in Christianity in Africa. You see this in Islam in Africa. As I said, there's a lot of dispute today about reformers saying that it's gone too far in accommodating local understandings. But I do think that any religion does that and historians of religion can see that much more dispassionately than practitioners do.

0:01:30:>>ROSEMARY PENNINGTON: You write a lot about the elites converting to Islam more quickly than the larger populous in sub-Saharan Africa. Why did that take place?

0:01:40:>>JOHN HANSON: I think it had to do with the mode of transmission. You had merchants buying large, who were coming across the Sahara and they were engaging in trade. Largely, the states in sub-Saharan Africa were controlled by elites who monopolize trade and so, therefore, those merchants coming across the Sahara were living in capital cities and so, therefore, they're engaged with elites oftentimes are secluded from the vast populations who are farmers or herders or others. And so, therefore, the elite had the opportunities to engage with those Muslim clerics. It has to do with the fact that trade was so important in the exchange and the elites had more obvious contacts with the merchants than let's say the rank and file population.

0:02:18:>>ROSEMARY PENNINGTON: You write a lot about this idea of reform that seems to be sweeping through Islam in sub-Saharan Africa. When you're talking about reform, what exactly do you mean?

0:02:29:>>JOHN HANSON: Well, reform is in the mind of the reformer and there is a important tradition within the Muslim heritage of reform and there is a sense that every hundred years they are going to be reformed to come and help bring faith into much more close alignment with what God would want and what the practice of Prophet Muhammad would be. So, therefore, what those reformers define as reform is what Muslims would say is reform. And I would agree that there are variations of what it is to be a reformer and that there are major disagreements about what it is. I'm studying a movement known as the Ahmadiyya movement that has origins in South Asia and has expanded throughout the world. Their understanding of reform emphasizes certain aspects of a progressive engagement with a Western tradition, that some other people who are reforming would say no, that's not what we should do. I think they're both reformers or all those are reformers and so I leave it to the Muslims who define themselves, what is reform? And then we can dispassionately disagree or understand, well, this is a certain kind of reformer, this is a different kind of reform. So, therefore, I would say that reform is in the minds of the reformers themselves.

0:03:35:>>ROSEMARY PENNINGTON: What about radicalization? When I was doing research on this, I kept coming across articles that were talking about how radical Islam, however you define that, is sort of increasingly becoming part of the sub-Saharan African experience, whether we're talking about Ethiopia or Sudan or Nigeria. Is radicalization taking place in parts of sub-Saharan Africa? And if there is, why? What's driving that?

0:03:57:>>JOHN HANSON: I would not say that there is a radical move. I think, for example, if you look at Somalia, there was a movement that emphasized Islamic law as a way to get beyond the conflicts between clans. I think that was a very effective kind of movement. Some American researchers thought that that was going to be radical. There was a very small faction within that movement that was allied with groups like al-Qaida. But I would say the larger movement within the Somali Islamist community was not necessarily radical in that regard. They were just trying to put society in a much more reformed context. And so, therefore, I think oftentimes, looking in from the outside, we can see radicals when they really aren't radicals from, let's say, village to accommodate others within society. And so, therefore, I'm reluctant to say there were radicals all over sub-Saharan Africa. I think that there are some people who were making a radical claim but they oftentimes, tend to be a very small group.

0:04:50:(MUSIC PLAYING)

0:04:56:>>MANAF BASHIR: This has been Muslim Voices, a production of voices and visions in partnership with WFIU public media from Indiana University. Support from Muslim Voices comes from the Social Science Research Council. You can subscribe to our podcast in iTunes or join a discussion on our website. Find us online at muslimvoices.org.

0:05:16:(MUSIC PLAYING)

IU Global

IU Global